After watching an interview with Tom Ebeyer, founder of the Aphantasia Network, I found myself nodding along in recognition. For about a decade now, I’ve suspected I’m aphantasic, at least in vision. After watching the video and running some tests, I’m pretty sure that extends to all sensory modalities. This has been confirmed through countless conversations with friends and family where I’m invariably the odd one out when discussing mental imagery.

What is Aphantasia?

Aphantasia is the inability to voluntarily create mental images in one’s mind. While most people can “see” a beach when they close their eyes and imagine one, I can’t. And it’s not just visual imagery – for me, it extends to all sensory modalities. This makes those annoying new-age “walking on a beach” meditations really boring for me!

This condition mutes the emotional memory of autobiographical experiences. That’s not to say I don’t feel emotions – when the interviewee mentioned his mother died in high school, I felt a deep but quick visceral sadness. But my remembering is more intellectual than sensory. I’m not very “past-oriented” and more “present-oriented”. I lack the ability to effectively perform mental time travel that others seem to experience.

Creative Process and Aphantasia

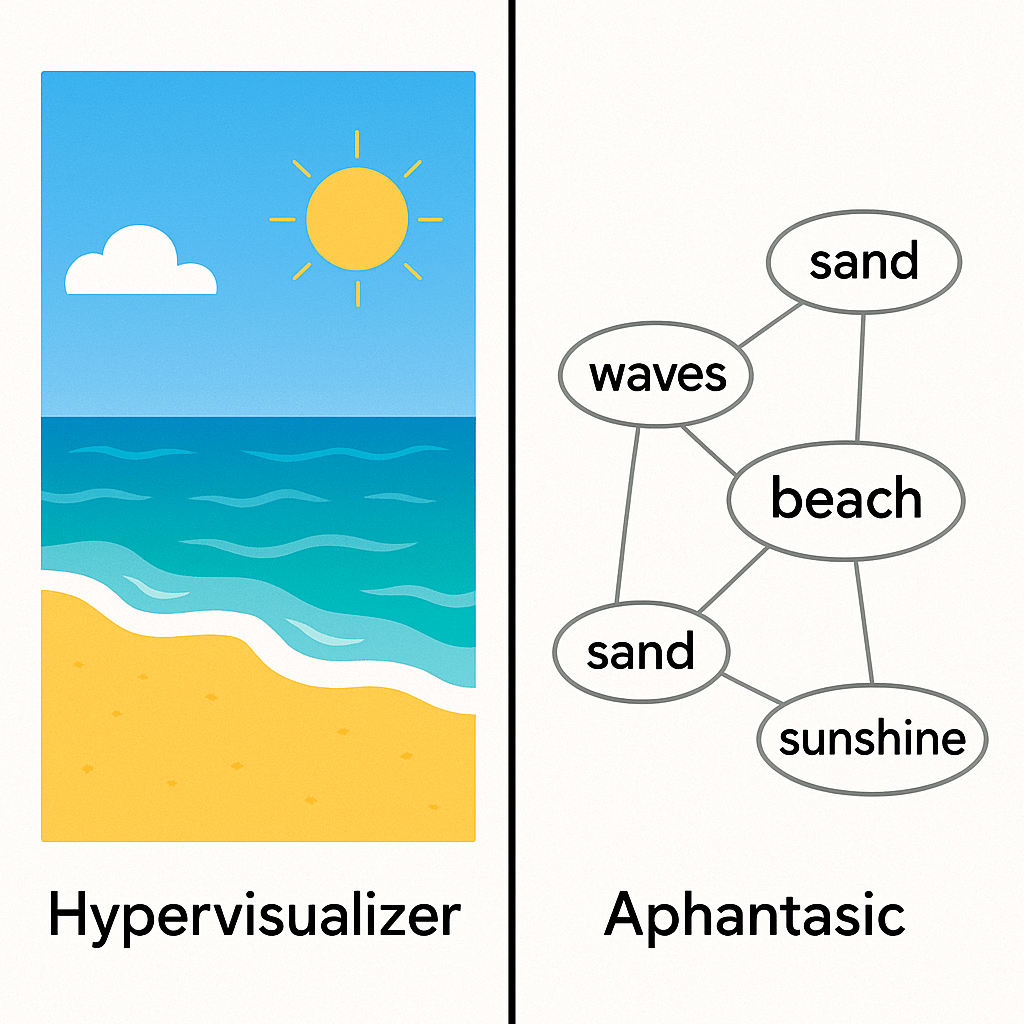

What fascinates me is that you can’t tell the difference between art generated by hypervisualizers and aphantasics. The process, however, is entirely different.

While hypervisualizers start with an exact image in mind and then try to recreate it (often feeling disappointed by the mismatch), aphantasics like me start with a feeling or something we want to explore. Creation becomes an exploratory process.

This mirrors exactly how I approach writing – I need to write to explore. I don’t know where it’s going when I start; I simply begin from a feeling and follow the thoughts that come with that feeling. These aren’t visual thoughts either. The closest approximation might be auditory thoughts – my own voice talking through the words, but typically at a faster speed with shortcuts. Writing things down actually slows the thoughts and requires more structure, punctuation, and occasional pauses.

I cannot picture a scene and then describe it in words. Rather, the description comes naturally when I think about a concept, through a non-visual thinking process that involves holding ideas in mind and combining them with other ideas as they emerge.

This exploratory approach to creativity appears in many of my journal entries, where I often start with a feeling or question and let the writing process itself reveal connections and insights. For example, in one journal entry I began with vague concerns about productivity and meaning, then used the writing process itself to clarify and structure these thoughts. What I thought at first was a writing technique I’m slowly beginning to realise is actually how my aphantasic mind naturally works. Know thyself is actually pretty challenging if it turns out your inner experience might be quite different from the majority!

Memory and Information Processing

Although I can’t imagine things I have just seen there is often a “shadow” of sensory experience in my memory. If I see a photo, I can describe it by remembering and holding aspects of what I’ve seen without actually seeing them, but this fades as quickly as working memory when something else comes in and replaces the entire mental stack. This isn’t so much recreating a picture in my mind as a “stickiness” of certain words and concepts.

The interviewee mentioned remembering dreams as stories, similar to remembering a story in a waking state. That’s definitely me. He also makes the world “real” and “concrete” by verbalizing internally – again, exactly my experience.

I was startled to learn that non-aphantasics can sometimes “see” their dreams for 3-4 seconds upon waking, where the dream and reality mix. This seems like a completely foreign experience to me.

Professional Inclinations

It’s probably no coincidence that I gravitated toward digital electronics, computing, and AI. These fields all involve things that have no real visual or concrete form. In these fields, you often have to build something to see it. The interview suggested there are more theoretical physicists who are aphantasic, and a general bent toward STEM fields among those with this condition. Although not touched on in the interview, there is also an overlap with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) – and this too is seen in the STEM bias.

I recall early in my career having problems with supervisors who would ask me to “picture it in my head” to describe something. When I said I couldn’t, they either didn’t believe me or looked at me with suspicion. This disconnect between different cognitive experiences seems widespread.

Later on in life I developed a career spanning patent law and AI development. Both fields value abstract thinking and formal representation systems rather than visual imagination. My interests and writing consistently show a comfort with analytical frameworks and structured approaches to problem-solving, which may be connected to how my aphantasic mind processes information. Again, I often took these as a given for everyone, but it might be that they are rarer than I think.

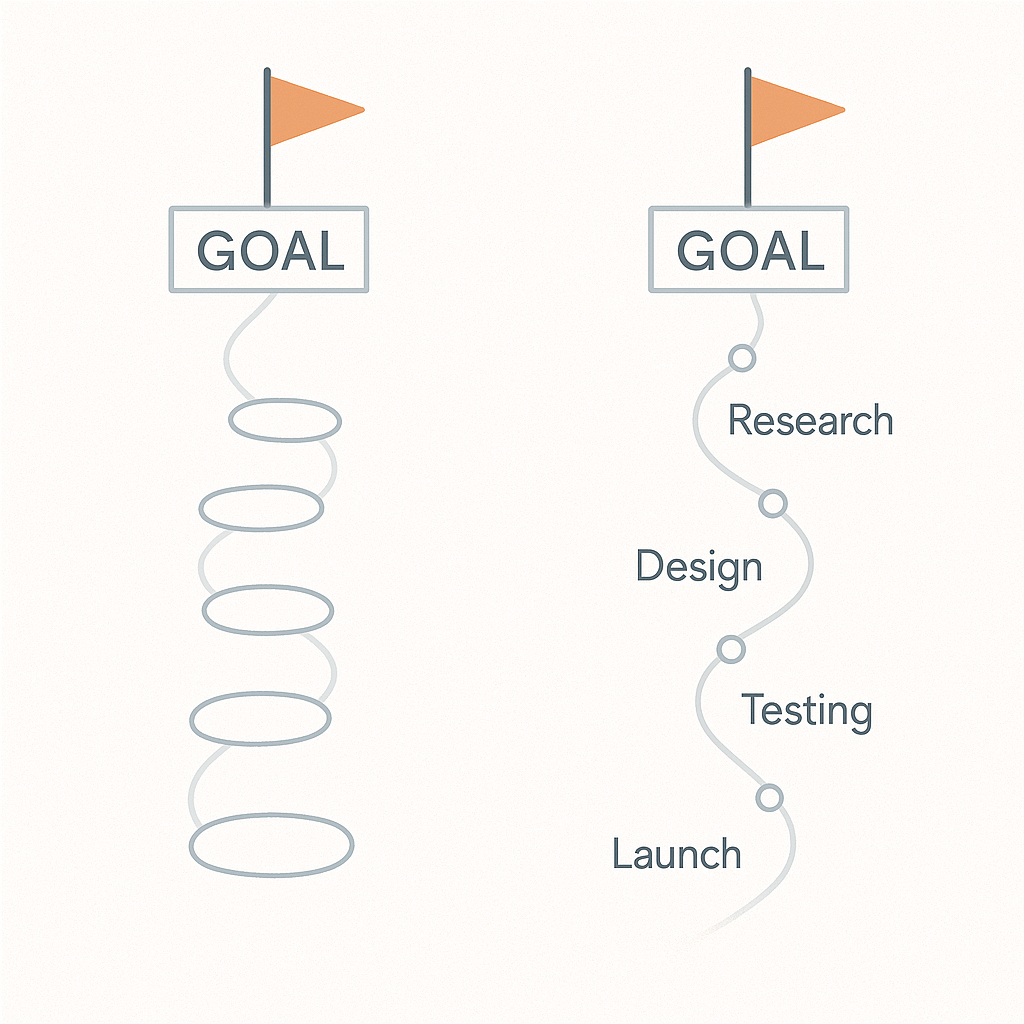

Motivation and Vision

The interviewer in the video asked an insightful question about drive and motivation: how do you create that without detailed visualizations of where you want to be? We talk about “vision” in our language when discussing goals – does that generally mean an explicit visual imagery for most people? I’d always imagined this to be an abstract concept, but do some people actually see a concrete image they’re working toward? In which case I’m wondering, do aphantasics require a different approach to goal setting? And I wonder whether my sometimes faltering motivation may be down to an inability to visualise outcomes in the future.

Emotional Connection

People with aphantasia often report feeling somewhat detached – because they don’t have strong emotional connections to mental imagery (as the imagery isn’t there), everything gets intellectualized to a certain extent. I’d say that’s also an issue for me in my daily life. I always feel somewhat disconnected – it’s normally a strange background feeling that you can’t quite place.

It’s also interesting because I’m drawn to both film and live music – hobbies where there is an immediacy of “now” experience where there is no need to imagine. With film I can allow someone else to be at the visual controls and find it easy to become immersed in the vision of another. With music, the sound fills your brain in an immediate now that is highly enjoyable at the time. Once the event is over though, I often find it hard remembering it. And photos and video never do it justice (which also helps stop me be one of those annoying people with their phone out). This all forces me into a very Buddhist-style “all we have is now” (which ironically I did see live last week and now can’t really remember).

I think it also has nudged me into analytical modes of thought. Oscillation between intellectual understanding and emotional experience is a recurring theme in my reflections.

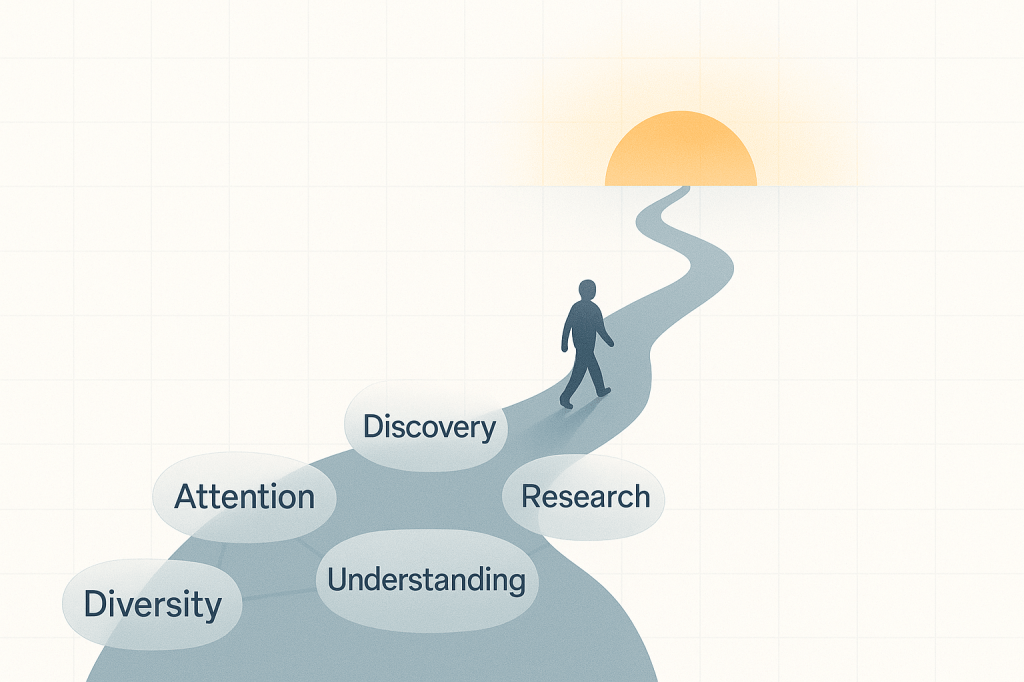

Attention and Discovery

The research suggests it’s easier for aphantasics to pay attention to the world around them, while others tend to go internal fairly often. This might explain why I often feel more attuned to external stimuli.

An interesting question: do aphantasics experience visual imagery subconsciously? Does that even make sense as a question? And does not being able to visualize motor imagery affect my ability to gain sporting skills and prowess?

Most aphantasics don’t know they have the condition – it’s invisible and subjective. How could you know your experience differs from others when you can’t directly compare internal experiences?

Research and Understanding

The interview mentioned that there are no “reliable” cases of “turning back on” congenital aphantasia. This is good to know in a way. Also the way people talk about “brain implants” tends to ignore entirely how neural connections, and thinking itself, works. The implication was also that there might be unreliable cases out there – the “self-help”, “self-discovery”, and adjacent “new new age” fields are full of rubbish. You don’t need to be true or accurate to have a best-selling book or blog post or viral YouTube video. Because the aphantasic brain is more attuned to attending to things in the world, it can be harder to switch off input – here there seems to be some overlap with autism spectrum disorder.

I find it particularly fascinating that the man who developed experience sampling (sending out beeps and asking people to record what they were doing just before the beep) concluded that people have hugely poor knowledge of their inner experience. We think we know what’s happening in our minds, but often we don’t.

Going Forward

Learning about aphantasia has helped me understand aspects of my cognitive style. It explains my approach to creative work, my relationship with memory, and even some of the disconnection I feel in certain social contexts.

Rather than viewing this as a limitation, I see it as simply a different way of processing information – one with its own strengths and challenges. After all, I’ve managed to build careers without ever “seeing” a single mental image.

Perhaps there’s something to be learned about the diversity of human cognition here. Our inner worlds may be more different from each other than we ever realized, yet we manage to communicate and connect despite these fundamental differences in experience.

(PS: Apologies for the slight assistance from Claude from my very quick and rough notes after watching the video – if it’s the difference between AI-assisted and nothing, I think the former is better?)

Resources

Aphantasia Network – https://aphantasia.com/guide/