[Disclaimer: in full BDF-AI mode, this blog post has been generated by: my phone bullet points + BDF event details + old blog posts on similar events + my review + tweaking. It means I can get something published in 30 60 minutes rather than a day. I do have jobs and kids. But some of it is still a bit LinkedIn cringe – sorry! :)]

I’ve just come back from the Bath Digital Festival, feeling properly energised and excited. The ‘Beings’ day on Thursday was particularly thought-provoking – a rich mix of presentations, debates and networking that left my head buzzing with ideas about where technology might take us and how we might better steer its course.

The Human and The Machine: AI’s Role in Our Future

What Does It Mean to Be Human?

The Big Conversation panel posed a central question that almost perennially plagues me: what does it mean to be human in a world increasingly shaped by AI? We’ve moved well beyond the straightforward enhancement of physical abilities. Now, technology challenges our cognitive skills, our creativity, and perhaps even our sense of identity.

What struck me was the stark contrast between the abstract discussions of AI’s potential and the practical reality. One panellist observed that whilst we’re possibly at the peak of the Gartner Hype Curve for generative AI, most businesses are still fumbling with implementation. As one speaker put it, “I was working at Board level with a UK subsidiary of a multinational corporation with 700 people – the Board don’t know about and haven’t used AI“. This contrasts with many start-ups I chat to, who are heavily AI-powered. That technology adoption gap feels familiar; a version of what William Gibson meant when he said the future is already here, just unevenly distributed.

Debate – AI & Mental Health – Net Positive?

The debate on AI’s impact on mental health in the tech workforce was particularly illuminating. Jim Morrison (tech strategist and founder of Nourished News) made a point that resonated with me – that predictive text, whilst seemingly innocuous, has been shown to produce shorter and less creative work. There’s something homogenising about these tools. As he put it, the “idea that you are good at something is diminishing – my kids can write code that’s just as good as the stuff I write, AI can write just as well as I can, if not better“. Does that mean we are at risk of “losing the love?”

Yet Joyann Boyce from InClued AI countered with the perspective that AI is allowing more people to write code, broadening access to traditionally exclusive skills. She argued that for neurodivergent individuals who struggle with certain forms of communication, AI assistance in writing emails represents genuine liberation.

I found myself nodding along to both perspectives. The question seems less about whether AI is good or bad for our mental health, and more about how we might develop a healthier relationship with these tools – one that augments rather than replaces our distinctly human capabilities. I definitely enjoy coding more when there is a shorter gap between idea and implementation, and I would say that at the moment AI feels more empowering than diminishing. But the Internet also felt similar in the early days. Will we have a choice to avoid the rot or is it inevitable?

Regulation – More Thought Needed?

Regulation came up several times within different sessions. I feel there’s sometimes a naïveté about how many people invoke regulation as a magic wand to fix whatever they don’t like about technology. One panellist astutely observed that we’re in a peculiar position where “businesses don’t want to be the first mouse that gets caught in the trap – they want to be the second mouse that eats the cheese.” Everyone’s waiting for someone else to get the first “AI fine” under new regulations, whilst marketing departments slap “AI-powered” on everything from sophisticated machine learning systems to basic autocorrect.

Dr. Nicola Millard from BT gave a refreshingly grounded keynote on “Humans + AI: A Recipe for Success?” She cut through the hype to focus on what actually works, drawing on her background in psychology and neuroscience, and with real experience in big first-line call centres. She spoke about acceptance of technology being rooted in our mental models – the way we expect systems to work based on prior experience. It’s not just about usability; it’s about trust, familiarity, cognitive load, and emotional response. These human factors explain why some AI implementations succeed whilst others fail spectacularly, regardless of the underlying technology’s capability.

Disability, Technology and Being Human

The session on Augmented Human Futures was particularly moving. Tilly Lockey, known for her bionic arms, delivered a compelling presentation that challenged conventional thinking about disability and technology. Owen Collumb, a Cybathlon BCI pilot, also provided a fresh perspective on working as a valued team member, rather than a medical subject.

What stuck with me was the profound reframing of disability, thinking: “Those with disabilities are our explorers, those on the frontiers, developing tech that will help humanity.” This isn’t just a nice sentiment – it’s increasingly evident in the innovation pipeline. Disabilities offer different ways of thinking and being that can show the way forward for everyone.

The panellists also critiqued what I feel is often a colonial or patriarchal approach of medicine – “telling people what they want, gatekeeping, and assuming.” Instead, they advocated for “working with someone rather than for someone.” It’s a subtle distinction that makes the difference in technology development.

A point that genuinely made me think was about consumer markets driving innovation more effectively than medical markets. “If everyone had a device, there would be a much bigger market and development would be quicker,” one speaker noted. The implication is challenging – should we be pushing assistive technologies into mainstream consumer markets rather than keeping them siloed as ‘medical devices’? But regulation is there for a reason and generally arises when things go wrong.

It was good hearing from Ben Metcalfe from the University of Bath on innovation – his view of the regulatory system is that it just doesn’t work for small scale devices, experimental prototypes and early stage products designed for less than 1000 users. Rather it is designed for large companies with mass market products, and the resources that are expected to go with this. This means many bits of technology with large-scale potential to improve people’s lives never makes it out of the development stage in the university lab into people lives. This is another problem with the implementation of regulation – typically only large companies with large profits can afford the full time roles that check and implement the regulation. But this is typically not where innovation arises anymore. Furthermore, many disabilities are unique, requiring tailored solutions – these don’t fit with the “single regulated product” cookie-cutter pattern applied in Western democracies.

There was a stark reminder of how fragile some of these technologies can be. A tale was told of an Australian retina implant technology that went bankrupt, forcing users to have their implants turned off, exemplifies the vulnerability of depending on proprietary technology for basic human functions. As we increasingly merge with our technologies, these corporate risks become bodily risks.

Community Technology and Alternative Futures

The evening event on “Tech for Community Futures” at the Museum of Bath at Work provided a refreshing counterpoint to the corporate and academic perspectives dominating most tech discourse. The crowd was noticeably different – more folk from charities and the third sector, less hardcore tech, more alternative ways of thinking.

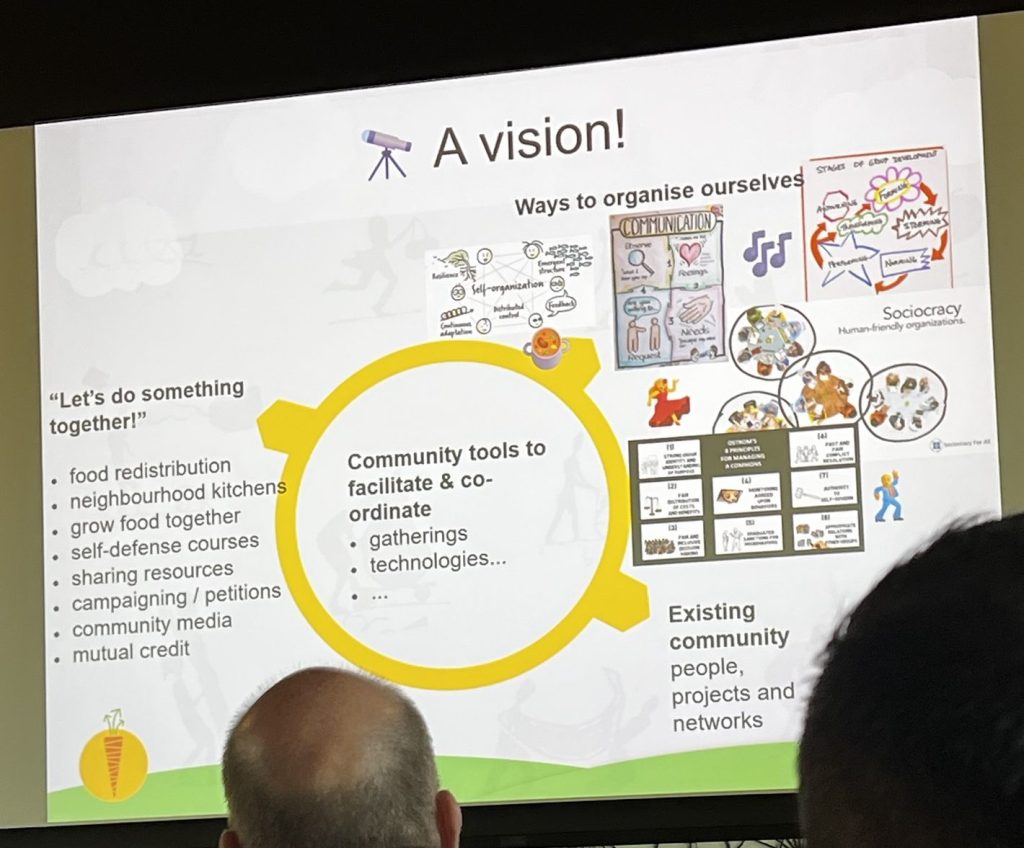

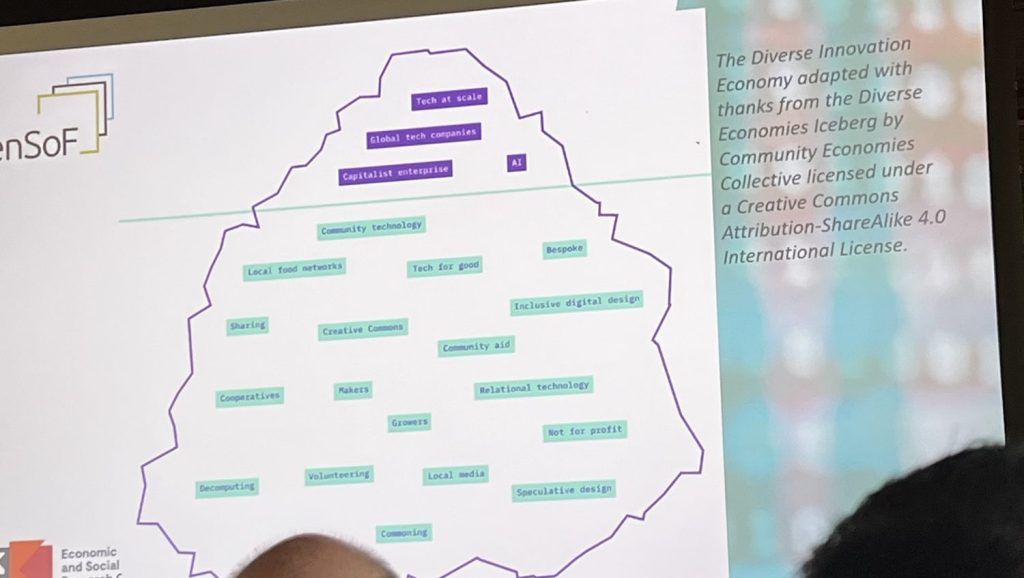

Matt Dowse’s research on community tech sparked some interesting conversations about how communities might engage positively with technology to navigate the challenges of sociodigital transformation. Nick Sellen, a tech practitioner from Bath interested in deeper economic and social transformation, showcased Karrot – a platform supporting groups that want to coordinate activities on a local, autonomous and voluntary basis.

What emerged was a vision of technology that emphasises sharing, care, networks, conversation, and need – rather than profit, scale, and disruption. It’s a model that feels particularly relevant for Bath, with its strong community ethos and blend of historical perspective and forward-thinking innovation.

I was particularly taken with Peter Lewis’s work on reducing reliance on centralised tech platforms by making self-hosted, privacy-respecting, and resilient alternatives more accessible. As someone who’s just finished Sarah Wynn-Williams Careless People – an expose of careless practices at Meta, I appreciate the importance of this work – and its challenges.

Reflections and Looking Forward

Overall, the festival left me with more questions than answers – which is precisely what makes it valuable. I’m particularly struck by the tension between the techno-optimism of the augmented human future and the more grounded, community-oriented approaches to technology. It was also great to catch-up with old connections and meet new ones. There was a particular buzz and vibrancy to the festival this year, and the inclusion of more creative elements from Bath Spa University worked really well.

The festival highlighted that we need both the ambitious vision to push boundaries and the pragmatic wisdom to ensure technology serves human needs rather than reshaping them to its own logic.

Bath seems uniquely positioned at this intersection, with its blend of engineering excellence (University of Bath’s Institute for the Augmented Human), creative institutions and industries (Bath Spa, theatre, music) , and strong community sector. What it lacks in raw scale compared to Bristol or London, it makes up for in cross-disciplinary conversation and quality of life that attracts thoughtful technologists.

As I walked back from the Museum of Bath at Work, I found myself thinking about next steps. The Byte Sized Cyber networking event I attended earlier in the week provided good connections to stay in touch with – mixing legal, regulatory and hard practical tech perspectives. I’m also keen to follow up with Bath Cooperative Alliance and explore bath.social on Mastodon. There’s clearly a vibrant underground of technological activity in Bath that deserves more attention.

I left feeling that the future of technology isn’t just about what we build, but how we build it, who builds it, and who benefits from it. In that sense, Bath Digital Festival wasn’t just showcasing technology – it was modelling a more thoughtful approach to technological development itself.

For a compact city, Bath punches well above its weight in technological innovation. As one speaker put it, remembering a Douglas Adam’s reference, “We’re at the 42 stage with AI” but that means we’ve maybe forgotten the question. Perhaps Bath’s contribution might be to help us remember what questions we’re trying to answer with all this technology in the first place.